Building off of Martha’s previous post, I’m going to discuss some challenges of mapping projects with old maps. Old maps pose challenges to digital projects. In particular, the spatial arrangements of many old maps don’t match modern day maps of the same area. A path made up of geographic coordinates (such as on Google Maps) is not guaranteed to be compatible with old maps. In addition, there is a fine line in many of these maps between maps and city views, especially in many early modern European prints.

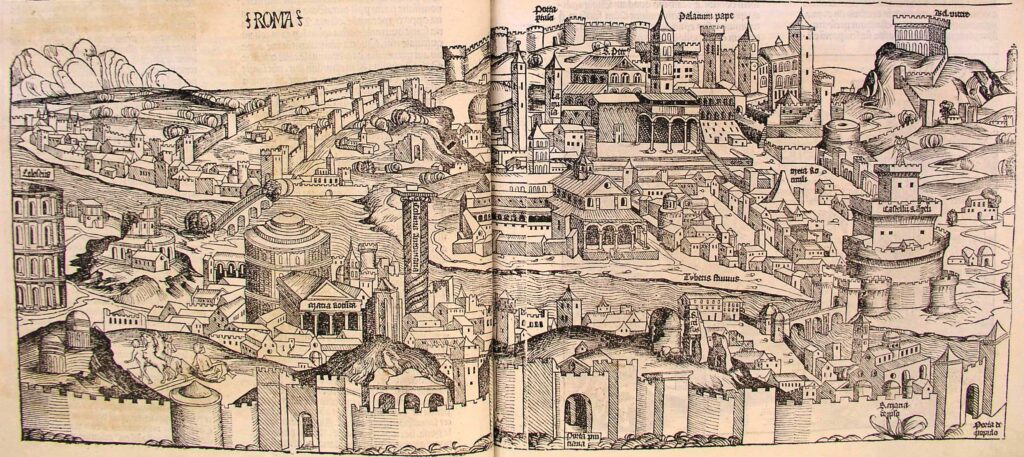

One example of these map/city-view that is useful to think with is the woodcut of Rome from the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle.

This woodcut image clearly shows Rome – in addition to the label (which I will expand a bit on later), there are many recognizable sites – the papal palace, the Castel Sant’Angelo, the Pantheon, and the Colosseum. It is not a simple city view – the geographic relation between these sites shows the general layout of the city. However, trying to plot a path (or even just points) on a georeferenced version of this map is not feasible.

Georeferencing warps the map image, trying to get it to fit the points on the image to relevant points in the real world. Sometimes this warping can be very extreme, especially for certain kinds of transformations:

The control points (which link the image to geographic points) on this map do not line up well, since the spatial arrangement of the map/woodcut image do not line up with their geographic locations. This image shows the difference between the points on the 1493 map and the present day map, shown as blue lines.

Another problem with a map like the Nuremberg Chronicle woodcut is that we don’t know what all the landmarks are. There are many church structures, but only a few are labelled. In addition, there are features that seem to be missing – for example, it is difficult to distinguish Tiber Island on the woodcut, which is a major landmark. Furthermore, the scale of the buildings pose problems. It is relatively easy to use the center of the Pantheon as a point on a present day map, but where on the woodcut image is the “center” of the Pantheon? In all, attempting to georeference and plot points on a map such as the Nuremberg Chronicle woodcut image of Rome is frustrating, inaccurate, and ultimately provides no additional insight. In fact, the extreme warping of the image makes it more difficult to understand the and the data represented in relation to it.

My attempt to chart a path on the Nuremberg Chronicle map

The closest point is the Colosseum – nothing else lines up very closely at all (the path is supposed to go from the Colosseum to the Pantheon, to one side of the Ponte Sant’Angelo, to the Castel Sant’Angelo, to the Vatican). The result is not illuminating and does not contribute any new knowledge, and in fact doesn’t serve either purpose well; it is difficult to interpret the Nuremberg Chronicle map, and it is almost impossible to know which landmarks are denoted by the path.

Can we trust the labels?

In the Nuremberg Chronicle, no, we can’t! Rome is clearly correct – the sites confirm the label. Other cities are like this, including, for instance, Krakow, which gives specific labels of a part of the city and reflects the city layout. However, for more minor cities, the Nuremberg Chronicle often uses the same woodcut for different cities.

In fact, the same woodcut is used for nine images (see below). These images include: Napoli, Perugia, Mantua, Ferrara, Damascus, Bena (I’m not sure what city this refers to), a German province (not sure about this one either), Spain, and Macedonia. While Italian cities may have similar styles, I cannot accept that Napoli, Damascus, Spain and Macedonia literally looked like these woodcuts. Therefore, not only do these images provide difficulties in terms of spatial alignment, but we also cannot always accept them at face value, because they may be no more than a generic representation of a city than a visual representation reflecting an actual cityscape.

Sources:

The color woodcut images come from the digitized University of Cambridge Nuremberg Chronicle (CC BY-NC 3.0): (the page numbers are: Bena 80r, Damascus 23v, Ferrara 159r, Macedonia 275r, Mantua 84r, Napoli 42r, Germany? 284v, Perugia 48v, Spain 289v).

The woodcut image of Rome is from the digitized copy in Morse Library, Beloit College. Last accessed 16 October 2017.

RBMS/BSC Latin Place Names File provided help with place names.